I always like the idea of reading more business books, but somehow that doesn’t often transition to reality as I tend to use my travel time to listen to podcasts, catch up on email or Twitter and I’m more likely to read a novel or a magazine before I go to sleep at night.

Even so, I have a few business books on the go at the moment and, over the last couple of weeks, I’ve been reading The Innovator’s Dilemma, by Clayton M Christensen.

It’s a bit old now (first published in 1997) and not the easiest read in the world as it gets a bit repetitive with it’s “tell them what you’re going to say, say it, tell them what you said” approach, nevertheless the author puts forward some interesting theories that are already making me think differently about some of the business decisions I’ve witnessed recently. In this post, I’ll highlight some of the book’s key points and then I’ll follow up later this week with my thoughts on current IT industry issues and trends.

The book is predicated on the idea that there are two forms of innovation in technology:

- Sustaining technologies foster improved product performance.

- Disruptive technologies often worsen performance in the near term, and bring to market a very different value proposition. Typically though, these are cheaper, simpler, smaller and more convenient.

In part 1, the author looks at why great companies fail:

- Sustaining technology innovations sound great – after all, everybody wants improved performance, don’t they? As it happens, no they don’t: sustaining innovation can lead to companies providing more than customers want or are prepared to pay for. This leaves an opportunity for new market entrants with disruptive innovations.

- It’s also true that customers may not want disruptive technologies, at least not until a market has been created by others. The problem for established vendors is that, by the time the market is proven, it’s too late (or too difficult) for them to adapt. On the flip side, Clayton Christensen highlights that it’s very rare for new entrants to succeed in marketing sustaining innovations.

- Another concept the book describes is that of value networks: these may be based on rank order of product characteristics but also on the cost structure required (e.g. margins, etc.). The principle is that technologies with attributes that are only valuable in networks with low gross margins will be ignored by those looking for high margin business. As companies grow, it gets harder to continue the same rate of growth so they start looking for bigger bets.

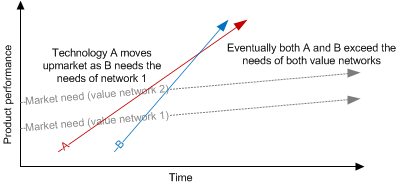

- In the book, Clayton Christensen describes a technology “S” curve of performance vs. time or engineering effort. The trick is for companies to switch technologies at the right point on this curve (where a new technology rises to intercept an established technology) but, whilst this works for sustaining innovation, it’s less applicable for disruptive innovation as each new technology has different attributes of performance. Consequently, new entrants get their commercial start in emerging value networks before invading the established networks.

- Established players can usually create the required technology to match disruptive entrants but it becomes a management decision about resource allocation (known as the “impetus to innovate”) – which would you do, given the choice of sustaining innovations to meet the needs of important customers or investing in disruptive innovations with small markets and unclear needs? And it’s this decision that, all too often, leaves the door open for others – maybe even for others from inside the organsation who leave to create a new venture.

- Christensen highlights that disruptive technologies don’t match the “S” curve and, typically they improve at a parallel pace with the established value network. Instead of looking for the point where new intercepts old (as with sustaining innovation), the aim is to look for the point where the emerging (disruptive) technology intercepts the market need.

- New technologies may well intercept the old ones if the trajectories are different and this allows new entrants to join established value networks (because progress has diminished the differences between technologies). Put differently, once two technologies can both meet a need, the fact that one can do it better ceases to be of competitive relevance.

- For established vendors, Christensen suggests it’s not a problem of being sleepy or of arrogant management – often the disruptive technology simply didn’t make sense (in their value network) – at least not until it was too late. It’s a lot easier to companies to move upmarket into established value networks, but harder to go down. Essentially, middle management will screen innovation projects from deep within organisation by only sponsoring those likely to succeed – i.e. those with a clear market demand. This market demand can be attributed to three factors:

- The promise of up-market margins.

- Upmarket movement of many customers.

- Difficulty cutting costs to move down-market profitably.

- This creates a vacuum downmarket for new entrants with disruptive technologies and cost structures that are better suited to competition.

Part 2 of the book looks at managing disruptive technology change:

- In addressing the challenge of allocating finite resources to innovation projects with unclear returns, one approach is to spin out a new organisation. This new organisation can develop new products without the constraints of the old business, then bring back its values back in house (perhaps replacing most of the old company) once established. It’s also possible to do this with organisational units within a company but resource allocation is a challenge and often fails. The key appears to be embedding independent organisations with different value networks – for example to be able to “get excited about a $50,000 order” when the company is used to $1m orders! Each organisation has to be free to persue its own customers as a separate organisational unit and to compete.

- Another point that Clayton Christensen makes is that leading in developing and adopting sustaining technologies gives no discernible competitive advantage. On the other hand, leadership in disruptive technologies creates enormous value. Effectively there is a trade-off, exchanging market risk (i.e. the risk that an emerging market might not develop) for competitive risk (entering a market against entrenched competition). Because markets that do not yet exist cannot be analysed, in order to confront disruptive change, it is necessary to plan for learning and discovery rather than execution.

- It’s also important to recognise that a failed idea is not the same as a failed business. It’s common for a business to abandon it’s original business strategy after implementation highlights what would/wouldn’t work in the market. Chritensen suggests that guessing the right strategy at the outset is less important than running out of resources or credibility before iterating towards a viable strategy.

- On the other hand, failed ideas are a different story when it relates to management careers where a failed idea/project can block career progress so we’re generally often unwilling to take on the risk of disruptive technologies. As failure is intrinsic to the process of finding new markets for technologies we have to plan to learn rather than plan to execute. Often this means using discovery-driven planning (identify assumptions upon which business plans/aspirations are based) to test market assumptions before committing.

- Markets for disruptive technologies often emerge from unanticipated success and Clayton Christensen suggests that discoveries come from sharing how people use a product rather than listening to what they say. In effect, he advises getting out of labs and focus groups, and creating knowledge from discovery-driven expeditions into the marketplace.

- Even if people have the capabilities to tackle innovation, the organisation in which they work may not. Clayton Christensen suggests looking at organisational capabilities in terms of resources, processes and values. In their startup phase, resources (people) are important to a business; later, the emphasis shifts to process and value. Even with change management, processes are not as flexible as resources (we can train people to be multiskilled) – and values are less so. If an organisation lacks capabilities the options are:

- Acquire a new organisation.

- Try to change processes and values.

- Create a separate, independent, organisation.

- In the last of these, physical separation is less important than a separate resource allocation process.

- As we experience performance oversupply, performance attributes change such that, for example, as a product meets market demand for capacity, size, reliability, price etc. become differentiators. When this is completely played out, the product becomes a commodity. Effectively, differentiators lose value when features and functionality exceed market demands.

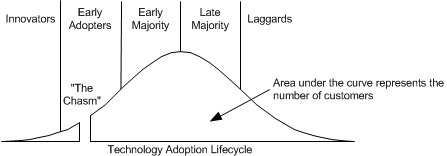

- Clayton Christensen attributes a customer buying hierarchy to Windermere Associates’ that identifies four phases of functionality, reliability, convenience and price. Another conception of evolution/technology adoption comes from Geoffrey Moore’s Crossing the Chasm

with innovators/early adopters, early majority, late majority [and laggards]. Using this model there is a price premium for early adoption, reliability is important for the early majority, and convenience for the late majority.

- The same attributes that make disruptive technologies worthless in mainstream markets become strong selling points in emerging markets – as disruptive technologies tend to be simpler, cheaper, more reliable and convenient. Therefore, Christensen suggests three strategies to deal with performance oversupply:

- Move upmarket: command a premium for better performance.

- Move with the customer, introduce new, disruptive technologies.

- Market to convince the customer that they need better performance.

There’s a lot more detail in the book and, although it can be heavy going at times. The writing style, together with notes at the end of each chapter betray the research/academic focus, which provides good accountability but is not easy to skim.

Throughout The Innovator’s Dilemma, Clayton M Christensen uses the disk drive industry as an example (along with other examples from the excavation and steel-making industries) but I can see some parallels with cloud computing too. In my next post, I’ll explain my thinking, but in the meantime I’d like to throw out a question:

Is cloud computing disruptive or is it a sustaining technology?

Finally, if you, like me, find these theories interetsing, you might also be interested in the Disruptive Library Technology Jester, who has produced a pocket-sized graph of the theory of disruptive innovation.

3 thoughts on “The theory of disruptive innovation (from The Innovator’s Dilemma)”